Who are we?

The Living Lab program is dedicated to enhancing and furthering the connection between UCSB’s faculty and researchers and the web of students, businesses, organizations, and other members of our community.

Fostering meaningful and productive interactions surrounding sustainability is what we’re aiming for—we want to write articles that peak your interest and expand your creative understanding of our world.

Whether this serves as makeshift office hours, inspiration for your next project or collaboration, or a fun morning read over coffee, we at the Living Lab hope that we can provide a reminder of the inspiring richness and complexity that our campus’s intellectual environment offers.

Read our articles below!

I arrived 10 minutes early to find Dr. Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval’s door slightly ajar. Scanning the room, I noticed the many book-packed shelves filling what seemed to be every wall of the room, save that directly behind his desk, which featured bright pop-art posters speaking (screaming, actually) for social justice.

He sprung from his chair by the window to greet me, shaking my hand and asking me to remind him why I, a sustainability columnist, was requesting to talk to him, an urban and racial studies researcher in the Chican@ studies department. His research on social movements highlighted a commonly overlooked aspect of sustainability, as the images of deforestation and recycling bins often crowd the spotlight of popular perception.

“I think Martin Luther King said ‘our lives begin to end the day we become silent about the things that matter,’” Ralph mused, leaning back in his chair. This, the struggle to achieve and maintain a sustainable political and social system, is the field I came to learn about.

| Since his time as an activist in the 1980s, Dr. Armbruster-Sandoval’s passion for social justice and commitment to helping these movements has fueled his career in academia. A huge issue for activists is their inability to conduct the data collection and big picture analysis that could help them act more effectively. Dr. Armbruster recognized that in many cases, despite the fact that “what was going on is wrong, it’s unjust,” activists and organizers, NGOs and other “people on the ground”, as he puts it, just don’t have the time to do research. “They’re kind of putting out fires.” |  |

Trying to take advantage of his relative luxury of time, Dr. Armbruster-Sandoval has dedicated his career to examining the mechanisms behind these efforts’ effectiveness, hoping that the data he collects will be useful to these movements. “The big question I was trying to untangle was,” he tells me, “it was a very practical one: why were they [the social movements] successful sometimes, but other times not?”

We began by discussing his first publication, Globalization and Cross-Border Labor Solidarity in the Americas: The Anti-Sweatshop Movement & the struggle for Social Justice, which examined issues to which most people easily turn a blind eye—whether out of frustration or fear. “As a student in the 80’s I was really interested in the human rights situation in Latin America and more specifically, Central America,” Ralph says, launching into a discussion of labor dynamics in that region.

Money is a huge factor in the power dynamics that social movements attempt to challenge. For big companies, unions are often a nuisance. During and after the Cold War, human rights abuses and massacres decimated labor unions in Latin America, drawing U.S. companies to countries like Guatemala and Honduras in search of cheaper labor. The first apparel industry sweatshops emerged in Central America in the early 1990s. Given that region’s proximity to the United States, exports soared, but when the Multifiber Agreement (MFA) was phased out, apparel companies sought out even cheaper labor in countries such as China. China was the “perfect” site for Nike, Reebok, Wal-Mart, and many other companies as this “workers’ state” routinely crushed efforts to form independent unions and raise wages and improve working conditions. Only several years ago, it was reported that Foxconn workers assembling products for I-Phones sometimes committed suicide based on the desperate situation they faced inside these factories..

“The accounting that goes on in terms of making these business calculations to make more bang for their buck is interesting to me,” Dr. Armbruster-Sandoval says, because though they’ve proven that they are capable of figuring out how to make the most money in any situation, “They won’t take into consideration how to benefit the worker. It’s ‘how can we actually exploit the worker for getting more return.’”

These companies’ dogged pursuit of the path of least unionized resistance threatens job loss for those who attempt to unionize or enforce workplace regulations, which makes unionizing seem like a desperate game of chase mixed with whack-a-mole. Thus, poor labor conditions are incentivized by the profit-making structure we currently have. But it could go the other way, Ralph thinks. To tackle this problem, social activists would have to think in terms of money. If all these companies care about is money, as he puts it, “hit them in the wallet.”

In his book he writes about how U.S. labor unions collaborated with Central American workers and unions to push for better wages and working conditions. Some of those campaigns have been effective, but gains have been fleeing and short-lived. Why haven’t they been more successful so far? Because they fail to present an achievable objective—an alternative to sweatshops that the movement could strong-arm companies into adopting. Sweatshops are terrible, a dirty underbelly of clothing companies like Nike. We all know that image somehow. That’s step one. (Spoiler alert: ‘rebranding’) But then we look away. We wear the shoes. Just do it. Don’t think about it. Maybe someone else will deal with it. There’s nothing we can do, right? We stay silent because don’t see a point in speaking.

At this point in the conversation, I think Dr. Armbruster-Sandoval and I both realized we were hitting on something very important, something with roots, some connection to a universal social phenomenon. It took us about 45 minutes more of squinting, sighing, laughing, and long, mind-wracking pauses to land on the idea that unites every issue we see today: how popular images both reflect and influence our political environment, and how the creation and use of imagery is central to the success or failure of social movements.

There are a series of steps that I gathered from our discussion, steps that every movement must take to successfully achieve systemic change. The movement must gain recognition for the issue, rebranding the subject as a problem worthy of attention. They can do this by appealing to compassion or to reputation: choosing the right one is important. Once the movement has successfully generated power through recognition, it must present an alternative to the status-quo, channeling this power into a solution. If they can’t effectively present a solution, they lose power to the pervasive, stagnating effects of compassion fatigue.

In trying to understand what makes social movements successful, Ralph has looked a lot at the power of imagery and how companies spend millions in creating a positive reputation for their brand. Popular perception of a company, issue or actor determines the direction and support of a movement. We discussed the concept of re-branding: creating an alternative image that speaks the truth and demands popular attention. If it is employed effectively, re-branding can be a primary driver of a movement’s success. “The idea is to attack the image,” Ralph says. Nike, for example, has been rebranded to a certain extent. People now associate the company with its use of sweatshops. This is the first step: drawing attention to the issue.

|

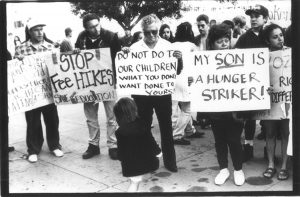

His most recent work, published last year, Starving for Justice: Hunger Strikes, Spectacular Speech, and the Struggle for Dignity. addresses how protesters catch and retain the public eye, and the extent to which some must go to drive change.

|

|

Even though women were starving, trying to scream out for change, the public managed to dismiss their significance, blaming mental instability as was the case for suffragist activists who went on hunger strikes in the early 20th Century. “If a man went on a hunger strike, he’s strong, he’s brave, he’s courageous,” Ralph tells me. He notes that “With women it’s the exact opposite. But they’re the ones who created this tactic! They were a huge part of it.” So the potency of an image depends on societal context. It needs to be so jarring that people won’t look away. “Sometimes activists talk about a toolkit,” Ralph says. Successful activists know which tools to use in which situations to make the biggest impact. In the multi-campus coordinated hunger strikes that Dr. Armbruster-Sandoval wrote about in his new book, the students knew that hunger strikes would be effective. In Ralph’s terms of the toolkit metaphor, “that tactic was there and they pulled it out.” |

Chicana/o, Latina/o students at UCLA, Stanford and UCSB all conducted hunger strikes in 1990s to protest of their campus’ consumption of grapes harvested by badly treated workers (they also had other demands, such as stopping tuition hikes, hiring more Chicana/o Studies professors, and recruiting and retaining Latina/o students). The students at UCSB, especially, felt inspired to draw on hunger strikes because of Cesar Chavez’s influence (he taught a class in IV theater before the hunger strike on this campus).

“I say that the hunger strike is a scream; it’s like a plea for attention. If you’re out in front of Cheadle Hall dying because you haven’t eaten, that’s what you’re doing. You’re screaming, saying ‘We’re willing to die, here, people.’”

Determining the potency of an image includes a sort of mental calculation concerning the interests of those in power. Do they have a heart? If so, break it. The student protesters knew how to do just that. “The chancellor would have to step over your body,” he says. That image breaks hearts. “They couldn’t ignore you.”

“The students were calculating,” Ralph explains, “thinking, ‘We think the administration has a heart, and they’re not going to let us die out here’ and they really didn’t.” The hunger strike movement was successful because the protesters used the right tool. They risked their own lives to call attention to an issue. In doing so, they represented two threats, examples of two tactics that leaders of social movements can employ to force those in power to change.

Successful social movements calculate the following: does my opponent have a heart? If so, then one must “pierce” it, as African American civil rights activists often did in the 1960s. If not, ruin their reputation and hit them in the wallet. The students in the hunger strikes did both indirectly. Firstly, by appealing to the hearts of powerful campus actors, they threatened guilt and emotional pain. Second, they posed a huge threat to the school’s reputation if they were allowed to die.

As mentioned earlier, big manufacturers don’t typically care about their workers. They care about money. No matter how ugly the image is, you can’t break Nike’s heart. So instead, a successful social movement targeting sweatshops would have to tarnish the manufacturer’s reputation, driving the consumers to buy from somewhere else, hitting the manufacturer hard in their soft spot: money.

Acquiring recognition is the first step towards pushing through ‘compassion fatigue’: a major roadblock for social progress, and probably the biggest threat to social movements’ success. It hurts for people to care sometimes, so if possible, they turn towards the image that’s easier on the eyes, ignoring the issue at hand.

|

Compassion fatigue is especially prevalent if the issue doesn’t get recognition, either because people feel that the issue doesn’t affect them or that the issue isn’t that important. Basically, as long as the image of the issue is faint enough that people can bear to dismiss it, they will. Change happens when the image becomes unbearable. As long as people see sweatshops as not their problem, the image is bearable for them, so they do nothing. |

Even if social movements are able to push through these recognition-related causes of compassion fatigue, people will continue to ignore an issue if they feel there’s nothing they can do to fix it. That’s why it’s so important to provide a solution. The hunger strikers succeeded because once they painted an ugly enough picture to secure recognition, these students levied their demand, providing the school with a way to avoid the threatened pain: stop supporting agribusiness owners that mistreat farm workers. The school could afford to do this—there were other foods to buy.

With sweatshops though, it’s another story. The competitive market drives all big manufacturers to use sweatshops. The solution is slippery, especially when the causes of the issue are hard to target. “When there’s a problem from a company’s point of view,” Ralph explains, “they shut down the factory and move somewhere else. That’s always been the ultimate trump card,” and this lack of accountability, he tells me, is a problem that hasn’t been solved.

So what if sweatshops are terrible? What are our options? “The inability to see a way out leads us to just go about our everyday lives,” he says. We don’t have popular competition that rises above the rest as a beacon of progress. “And I think that’s because we don’t really have a viable option…go to the thrift store, or don’t wear any clothes,” he laughs a tired laugh. Until sweatshop activists can provide and advertise a way out, it doesn’t matter how ugly the image they paint is if people don’t see change as viable.

He sighs, “One wonders if anything will produce any change.” By the end of the hour long interview my head is spinning. Talking with Dr. Armbruster, though, has instilled in me a new understanding of how social movements work, and in doing so has made change seem possible. While perhaps more complicated, social change no longer seems like an infuriating game of chance. And what is that they say? Knowledge is power? Knowing how change works gives us more power to enact it. As I leave his office, this thought gives me hope.

©2018 Natalie Overton

Making the jump to becoming politically involved is hard. For researchers, especially, establishing when, and how, and to what extent to apply knowledge in a helpful way outside the office is challenging. Until now, this uncertainty has kept Dr. Casey Walsh from applying his research to the wider public.

Although he spends a lot of time outside the office conducting research, whether in the field or sifting through archives, Dr. Walsh finds that the major challenge is applying this research to governance. “It’s easier to control,” Walsh tells me, “I gather all the data, I have it all in my hands, I sit in my room…being part of a process and failing on things, trying to get people to understand… you can’t control that.” The desire to help eventually outweighs the fear of not having control, and that’s what prompts action.

|

“I think we all do that, we see something that’s not working and we want to make it work… if you’re trained with this big critical perspective, then you have these tools to understand the big picture, and it really does take an exercise of creativity to say, ‘what can I actually do in a concrete setting?’ And I think most academics, if they feel that responsibility, battle with that.”

In 2014, Governor Brown signed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), the piece of legislation that inspired Dr. Walsh to make the leap into the realm of active politics. SGMA establishes a system of representation throughout California designed to create specific sustainable groundwater policies. In the SGMA process, everyone is spoken for by someone. The water agencies are supposed to represent their rate payers, and everyone who lives outside of that, in the counties, are supposed to be represented by the county governments. |

As it happens, some voices are heard much more clearly than others, and this relies a lot upon factors like money and political sway. Walsh figured that now was the time to throw himself into the mix, to help as best he could. “I like things to work right,” he says, “When it gets to water, and money, people are going after all they can get for themselves.” Water is important to everyone, but if left to its own devices, our current system would guarantee that water’s governance would be left to the richest members of our society.

Upon becoming involved in two very different locations, Cuyama and Paso Robles, Walsh noted that the assumptions supporting SGMA’s democratic representation system are flawed. Assuming everyone has the same ability and access to participate is dangerous. It allows us to rest easy thinking we’ve done the best we can—we’ve established a democratic system—and thus disregard everyone who doesn’t have the privilege to work this system. In short, the same democratic process works very differently in different areas.

However, Walsh tells me, “that relies on whether the counties have set up active engagements with their constituents,” and he adds, “I don’t think they have, in many cases.” There are 4 counties in Cuyama and they’re all present. The issue here, he says, is the lack of a culture of citizenship. “The county doesn’t really have anyone to interact with,” he says. “And that’s probably the problem with most counties across california. Most people aren’t going out of their way, they don’t even know about it.”

“Is it the job of the county to go out and create consciousness and capacity among the population of the importance of their exercising citizenship on groundwater politics? I think it’d be great if they could…”

“Now, I actually go to meetings, talking to people involved in the process of regulating groundwater that has not been regulated in california, almost at all, until now.”

Cuyama is very intensive on agriculture, and is home to several big organic farms, yet it’s a food desert: the people who live there often have to drive 45 minutes to get to the nearest supermarket. Cuyama has about 1,500 residents, the town of New Cuyama has around 800. The big farms have lawyers and researchers and PR people, all of which allow them to make a plan for the water that suits their interests.

| Residents of Cuyama, however, are often missing from the audiences of public meetings. “Very few people go to the town meetings, even though they’re open, they’re noticed and everything,” Walsh says. This could be due to a lack of time, interest, or topical knowledge. This means that the local water agency, which has about 250 ratepayers and thus can barely cover its own bills, has a lot at stake but can’t bring much to the table. |  A newly constructed expansive irrigated vineyard in Cuyama PC: Dr. Walsh A newly constructed expansive irrigated vineyard in Cuyama PC: Dr. Walsh |

There are two dimensions to this problem: stake, and participation from the population. Theoretically the two would go hand in hand, but in many cases they don’t. In Cuyama, even though the local water agency has a lot at stake in determining the new legislation, it’s missing the participation. Though the SGMA system is built to provide structural opportunities for participation, these often aren’t taken. Reasons range from “I can’t go to the meeting because I don’t get out of work until after it’s held” to “I don’t speak the language that meeting is held in”.

The Paso Robles population, on the other hand, was politically engaged before any laws were passed. This active engagement means that the people of Paso are much more likely to benefit from water laws that represent them. Concerning his role in different locations, Walsh says, “It really depends what the social field looks like in each case,” so if he’s in Paso Robles, “I don’t have a lot to say really, I’m just watching.” He adds, on the other hand, that “in Cuyama, there’s not that, so I go to the meetings, I give comments, because I feel like it’s just not as robust a citizenry in that area.”

The vast differences that he observes in the meetings are illustrative of the flaws in the application of this ideally democratic system, because, as Walsh notes, the application falls through when the baseline assumptions aren’t accurate. “A lot of institutions that we have managing commons are based on a different set of premises about what society looks like,” he says. Everything from social equality, access to resources, and participants’ assumptions about how their individual benefits align with wider social benefits—all of these establish a certain expectation, an optimal environment, in which democratic systems would flourish. Here, then, an environmental justice issue ties into a political one: the system we are using to manage our common pool resources is built on assumptions that don’t apply to many populations throughout California and the US in general, so we can’t expect it to work perfectly (or effortlessly) every time.

Firstly is the assumption that everybody knows the law—that people know their rights and how to argue for them. If they don’t, they’d have to hire someone who does, and this leads into the second assumption, that people have resources in the form of time, or money, often both. Working people in Cuyama, for example, might not have time to attend meetings or even research what they need to know to educate themselves on the technicalities of the law. Meanwhile, in Paso Robles, a large part of the community is retired, wealthy and well educated. They have the time and resources to fully participate in the democratic system.

Another requirement/assumption is engagement. “Where you see people really getting mobilized is small property owners whose shallow wells are going dry,” Walsh says. “A lot of people in Paso think of water as a part of the property, as a property right.” They’re subsequently more engaged, attending meetings and taking initiative. Seeing water as a right is a huge factor in determining political action.

In Cuyama, people often don’t own their land. They pay rent. So for them, water is just a number on their monthly bill. They live on the land; they don’t feel like they have a right to it. Thus, they might not even recognize it as an issue they should fight for, much less something that they can control.

Casey Walsh’s work is usually more analytical, so naturally he is able to lay out all the facets of this immensely complicated social/political/economic/environmental issue for me. His research extends to the control of land, labor, capital, and water on the border of mexico. Through all of this, he can recognize repeating patterns. “Powerful local agents continue to be powerful,” he says, “and continue to exercise more control over this process than those who have less.” The groundwater agencies can’t do much to counter these local agencies if they don’t have the popular engagement to back them up. In those cases, it’s the actors with more resources that get a voice.

The final piece of the puzzle is that the state does essentially have veto power over plans.

I ask him if it’s likely that the state government will substitute somehow for this critical lack of engagement by vetoing plans that seem to be one-sided. “We haven’t gotten to that point yet, so we don’t know how it’s going to turn out,” he tells me, adding, “I feel like we’re losing a big opportunity if that’s our game. If our play is to hope that the state is going to slap the hands of people who don’t care about citizenship, then you’re too late. Citizenship has to be exercised in the whole process. It should be there from the very beginning.”

©2018 Natalie Overton

The human relationship with nature is one of the most fascinating aspects of anthropology, as Dr. Hoelle continues to discover through his studying cattle ranching dynamics in Brazil. Our view of nature as both a canvas and a medium for human expression quietly permeates our everyday lives. From eating a celebratory steak to admiring the expansive manicured lawns in wealthy neighborhoods—we associate social status and identity with our ability to tame and utilize nature.

Jeffrey Hoelle is currently an associate anthropology professor at UCSB, but walking into his office I felt like I was in a rainforest. The deep blue walls and the palm tree lamp drew the room closer to us; it felt like a separate world, an escape from our conventional perception. This office fit him perfectly, as his work centers around understanding the lives of people in different cultures and their relations with nature. It requires a major shift in perspective to see why people do and believe different things, how value is so subjective, and how different societies build off that fundamental variation. To think the way Dr. Hoelle thinks is to part from your own learned values and knowledge in order to submerge yourself in another lifestyle. It felt like I’d not just left the HSSB hallway; I felt like I’d left the country.

His book, ‘Rainforest Cowboys: The Rise of Ranching and Cattle Culture in Western Amazonia’ came out two years ago.

I asked him about his introduction, which was John Steinbeck-like: the kind of text that sweeps you into the writer’s position gazing out a window, looking at the landscape like an old friend, full of warmth and fondness and curiosity.

He spent a lot of time in Acre, a wedge of Brazilian land nestled between the borders of Peru and Bolivia. Historically home to rubber tappers and indigenous peoples, Acre was being quickly overtaken by cattle ranching. During the 1970s and 80s, rubber tappers resisted the ranchers, but cattle raising continued to expand. “From 1998 to 2008, the count of cattle in Acre itself increased by over 400 percent, the greatest increase in all of Brazil,” his book notes. And a significant portion of this growth came from those with no history of cattle raising, including the rubber tappers themselves.

“This is what I’m trying to understand,” he tells me, leaning forward, “What is this dream of owning cattle that people have that drives them to seek out and raise cattle even when it doesn’t make economic or ecological sense?”

Here comes his buzzword: “Cattle culture.” As Hoelle defines it, a collection of “ideas and cultural practices that indirectly and directly valorize a cattle-centric vision of rural society.”

Cattle are worth more than the forest, both economically and culturally. His term “cattle culture” emphasizes the fact that in order to fully understand this shift we need to address the cultural importance, first and foremost. “That’s really what’s missing from the study of amazonian deforestation but also from a lot of environmental problems,” he tells me, “culture in general tends to be absent from a lot of our analysis of why people destroy nature or over-consume.”

This is especially relevant in developing policies aimed at disincentivizing amazonian deforestation. Without attending to cattle’s cultural value, policymakers end up passing legislation that just doesn’t work. “There are policies that encourage people to transform forest into pasture, either through subsidies or indirect incentives,” Hoelle says, “even if they are intended to preserve the forest.” The fact that people will navigate legal constraints to effectively turn a policy on its head indicates that cultural value plays a vital role in the rise of the cattle industry, one which cannot be ignored.

As the cultural and economic value of cattle raising has skyrocketed, the rubber tapping lifestyle in Brazil is shrinking. Traditionally, rubber tappers would live in allotted portions of the amazon rainforest, harvesting brazil nuts and tapping rubber to meet certain daily quotas. Now, however, most of this rubber tapping happens in Southeast asia on big rubber plantations. “It’s sort of that rationalized production where you go tree by tree,” Hoelle says of the much more productive method that has essentially pushed Brazil’s rubber production out of the international market.

Brazilian rubber tappers have traditionally maintained biodiversity, recognizing the value of intercropping and maintaining the forest to stabilize their crop. “That’s what forced the rubber tappers to preserve the forest,” he concludes, “because they needed these buffers between the [rubber] trees that had a value. But rubber doesn’t have a value anymore.”

This is where the consistent and reliable economic value of cattle raising comes in: “If they had cattle they had the assurance of a piggy bank—something they could sell whenever they needed the money.” This kind of economic security is welcomed by parents raising children. Being able to provide for one’s family and have a steady source of income has its own cultural value, especially in the face of the modernizing movement rolling through the Brazilian countryside.

This goes against maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which indicates that only richer people would prioritize preserving nature. It doesn’t take into account the cultural ideals that influence our priorities—for these brazilians, the rich want to consume meat and show off. The hierarchy, something we all learn when studying basic environmental policy, assumes that the environment will become an ideal objective at some point. That might not happen. Priorities are influenced by culture, and as long as our culture so deeply values beef consumption, our economies and policies will follow suit.

At this point, our conversation has taken a sociological turn. In what ways is meat tied into our social identities? “There’re these ideas of being a strong person, or a strong man, and that’s intimately linked with beef, especially.” Consuming meat is masculinized, and being consumed is feminized. “In Brazil these ideas of masculinity, of being modern, of being strong, they’re all very much tied to what you eat,” he says, and this understanding of men as consumers, tamers, developers, modernizers, and dominators translates directly into how we relate to our natural environment. “Although you may find the forest beautiful or environmentally important, people there see it as this dark, dirty, backwards space of animals or people who are less modern or developed.”

The landscape we produce reflects something about who we are. And it’s not just in Brazil. “Even though we are searching for sustainability in some ways we nonetheless continue to judge people based on the extent to which they actually impact or shape nature,” Hoelle reminds me. Yards are just one example: having a nicely groomed one suggests you’re responsible and trustworthy.

“We’re very attached to this idea of a perfect landscape. This idea of making a mark on nature, it’s key to where we got as a human society… But we can let off the gas now, in fact, our survival depends on it.”

To take it a step further, people who shape their surroundings are more…human. “In America, the landscapes that people create are really linked with how they’re seen on an evolutionary scale,” he says.

Thus, in Brazil, agriculturalists and cattle ranchers especially “feel that they’re bringing civilization to the frontier, displacing those who have had a lot of time to live in this area and not proven that they are worthy of using this land in a way that’s productive.”

So what’s the solution? How can we protect the environment, taking into account this strong cultural drive to ‘use’ it? Some policies have essentially paid people to not use their land, and while this may work in the short term, it comes ridden with potential pitfalls.

“If that is more profitable than cattle raising then that’s one thing,” he says, “but then you’re putting a value on the forest,” rewarding big landowners. This incentivizes buying more land, so eventually the rich would just buy up all the land, and we end up in a situation where a very few people own most of the land. Where does everyone else go?

“It’s all linked. You can’t really have sustainability unless you have equality,” he emphasizes. “If some people, because of race or class, are above others, then you’re going to continue to have the same relationship of domination that’s also expressed on the environment.”

A few questions about cattle raising in Acre, and we’ve spiraled once again into the discouragingly complex and interconnected web that is The Big Picture. Perhaps that’s how all conversations between a political science student and an Anthropologist will end.

“It’s fun, and sad, and hard, but it’s cool to produce the knowledge, and work towards a better understanding,” Hoelle says of his existentially challenging career choice. “ In anthropology it’s really hard because we start with the people and we try to understand them without talking in black and white terms, because these people are normal and they’re just doing what makes sense.”

Becoming so immersed in different cultures that you have to abandon many conveniently subjective value systems seems to be what he loves to do.

©2018 Natalie Overton

Dr. Herb Waite, Distinguished Professor of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology here at UC Santa Barbara, has dedicated his life to the childlike curiosity that drives fundamental science. With his emphasis on biology, his recent research (conducted out of his lab, the “Waite Research Lab”) centers around the small but impressively complex holdfast systems within the mussel, namely how these creatures latch onto the wet dirty surfaces of their underwater homes. If you’ve ever tried to wrest a mussel from its rock at the beach, you’ll understand how tenacious these little shellfish are. Their adhesive threads require enough yanking force that when finally broken can send a small child tumbling in the opposite direction, triumphant though slightly bruised, mighty mussel in hand.

Mussels can make as many of these incredible adhesive threads as they need to in their lifetimes: the entire process of growing and adhering one to a surface takes them under five minutes, a speed matched only by spiders’ web-making.

This process inspires and motivates Dr. Waite’s research into these complex biological processes. Dr. Waite and his group of grad students, post-docs, and collaborating faculty study the mechanisms behind the whole thread, a complex stack of proteins that ultimately connect with the mussel’s tissue. They’ve characterized 25 different proteins in the threads, each with individualized functions and unique timing during deposition, he adds, “march to the beat of this little process that the mussel is using.”

Mussel’s adhesive properties are a more sophisticated and less wasteful version of dentists’ techniques. Lying in the dentist’s chair, you might notice that the dentist dries the surface of your teeth before attempting to use an adhesive. However, this act of drying, whether using air or alcohol, is never complete and risks damaging the cells needed to keep the tooth and gum alive. As Dr. Waite notes, “there’s always collateral damage with procedures like that.” The mussel’s adhesive mechanism doesn’t require any sort of drying, though it does kill the bacteria at one point to prevent them from eating away at the adhesive proteins it creates.

| The aforementioned dentist would love it if they could get your braces to adhere without damaging the protective cells on the surface of your teeth and gums. That’s why dentists and many others in the medical world are excited about a key player in this process: Dopa. This amino acid is created by the mussel and is prevalent in its adhesive tissues. This is essentially the same compound as L-Dopa, the chemical whose absence is linked to the neurodegeneration associated with Parkinson’s disease. Unlike L-Dopa, however, Dopa is not a free amino acid—it’s a modification of tyrosine in adhesive proteins. Dopa is adhesive and researchers have found that the more Dopa that is included in an adhesive protein or polymer, the more adhesive it is. |  |

Engineers at Northwestern University in Chicago conducted a study in which they took a single molecule of Dopa and measured the strength of its’ adhesive. “Engineers are accustomed to reducing the complexity of systems so that simple questions can be asked and tested,” Dr. Waite says. However, biologists take a different approach: “We suspect from experience that reducing the complexity of the system too much will lead to an answer that is biologically irrelevant.” That’s why throughout his career, Dr. Waite has taken a more holistic approach in his research.

“Really, that approach has nothing to do with sustainability,” Dr. Waite comments on the Chicago study. His reason? The engineers weren’t looking at the chemical context in which the mussels were performing this adhesive process. For example, Dopa is typically very prone to oxidation. When Dopa is oxidized, it’s very good at cohesion, namely, sticking to itself. However, when it isn’t oxidized, it’s great at adhesion, that is, sticking to another surface. In this sense, this one residue can go in very different directions: adhesion or cohesion, depending on its local environment, which Dr. Waite refers to as ‘the chemical context’.

Even examining how the mussel maximizes the usefulness of its resources shows us that we have a lot to learn from these animals. “What’s always delighted me about this ‘consumer product’ that the mussels make,” Dr. Waite says of the mussel’s threads, “is that even when it becomes obsolete, it perpetuates the natural order of things.”

Why is balancing the oxidation of Dopa so important for adhesion? During detachment, the center of the mussel’s adhesive plaque comes up off the surface (rock, bridge, another mussel, you name it) thus allowing the local interfacial pH to equilibrate with the ocean water. Under normal circumstances, this pH shift would lead to Dopa oxidation. However, the mussel actually produces an antioxidant to protect its plaque tissue from oxidation during “off” cycles so that the Dopa can rebind during “on” cycles, thus prolonging the plaque’s functional lifespan.

Dopa-containing plaque proteins detach and reattach from surfaces thousands of times before they eventually become brittle and fail, only to be replaced by new plaques and threads. Failed plaques litter attachment surfaces though their presence is transient as they are degraded by the ambient ecology. Reuse is common in nature, though notably rare in human behavior: few of our products are designed to have a purpose beyond this short functional lifetime, and most of what we produce and consume becomes obsolete but remains to vex us.

“I like this fantasy that plastic grocery bags could be re-engineered to be more like mussel threads or the leaves of deciduous trees”, he explains the life cycle of a leaf—how when it falls and is no longer used to convert light into energy, it supplies trees, microbes and decomposers of all kinds with the nutrients they need, thus still serving an equally important purpose beyond its functional lifetime.

Dr. Waite is an adamant defender of research for the sake of understanding the entirety of his subject, cringing at the thought of the profit-driven treasure hunt for ‘useful technical applications’. So the question “what are the practical applications for your research?” worries him. “I’m trained to be a basic scientist,” he tells me, “and that question is coaxing me to become an engineer. Does that mean that all basic scientists need to become engineers in order to survive? That would be very sad.”

It’s not that he isn’t interested in finding sustainable solutions in natural processes, rather it’s the fact that many people approach science through a product-oriented lens that bothers him. “The public seems to think that a scientific project does not merit support unless it has a very useful application attached to it,” he tells me. But he doesn’t buy it. “Doing any science extremely well provides us with new concepts that then are part of the encyclopedia for remaking our world.” That’s a beautiful analogy that points to the faults and gaps in knowledge and thus the increase of waste, inherent in the reductionist point of view.

We can expect to see more of what Dr. Waite calls fundamental “blue sky” science. “We can’t afford to lose our childlike curiosity. For example, I can talk about squid beaks to kids and they will always be fascinated,” Dr. Waite shares. As we get older, many of us lose our sense of wonder about the world, and we’re more at risk of falling into the exclusively application-oriented point of view. “Adults tend to think that if research leads to a new kind of toilet bowl or something then, and only then, will it have value,” he sighs. But if we can fight deterioration in imagination, there will always be hope. And this hope is what matters to us in the sustainability world: open, imaginative minds guarantee that we won’t miss important solutions, and that we will hold a central place in our collective conscious for the holistic, waste-not-want-not approach that nature inspires in us.

———-

Dr. Waite’s note: I have collaborated with UCSB engineers since 2007 via a NSF-funded MRSEC project in MRL, “Bio-inspired Wet Adhesion”. This project has allowed me to maintain my “biology first” philosophy in collaboration with engineers like Jacob Israelachvili, Glenn Fredrickson, Craig Hawker and Megan Valentine, and chemists Alison Butler, Joan Shea and Songi Han. This diverse ensemble tested the hypothesis that, even if your research priority is creating new technology, superior technology-translation results from a more comprehensive and fundamental understanding of mussel adhesion biology. The answer is a resounding yes – our efforts are the envy of MRSECs nationwide.

©2019 Natalie Overton

This article is, in my opinion, best introduced by a few words from the crustaceous American sweetheart, Sebastian the crab. “Under the sea~under the sea~Darling it’s better down where it’s wetter!”— these lyrics run true now more than ever.

Achieving food security is exciting. It challenges us, as humans, to do what we’re best known for: adapting. We’ve all seen the changes that have reshaped our climate. Usable agricultural land is running out. Faced with a growing world population, we are challenged to feed everyone and to do so in a sustainable way. Dr. Hunter Lenihan and many of his fellow researchers turn to aquaculture as a new frontier, teeming with opportunities for innovation and sustainable solutions.

A researcher and professor of marine and fisheries ecology at UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management, Dr. Lenihan’s research spans oceans from Norway to Santa Barbara. “This is the blue revolution,” He tells me at the start of our interview, referencing the green revolution of years past. Indeed, aquaculture production has doubled from 60 to 120 million tons in the 30 years between 1970 and 2000, and has shot up to over 140 million tons in the last decade. At this rate, aquacultural production is quickly outphasing that of traditional fisheries. This is great news for species like dolphins and octopi—common bycatch of capture fisheries. Aquaculture doesn’t take from wild populations, so it doesn’t disrupt food webs, damage habitats, or kill animals we don’t mean to kill. When doing aquaculture right, we cut some of these negative impacts out of the equation. As we move into this new phase, this blue revolution, we must tailor the production to fit our goals: food security, sustainability, and environmental consciousness. Dr. Lenihan poses the question that sets the tone for the rest of the meeting: “How do we learn from the green revolution to make a blue revolution that’s more sustainable?”

He hopes to hit the sweet spot of widespread sustainable protein production by addressing disease prevention, increasing the protein feed to product ratio, and by transitioning to vegetarian feed sources. Disease, at least in my mind, is the first red flag that pops up when I imagine a future that relies heavily on aquaculture. We know that diseases spread rapidly when we raise large amounts of animals together very quickly—that’s a lesson we’ve learned from agriculture. In poorly executed cases of large scale aquaculture, the dense fish populations become breeding grounds for parasites and infections, which can infect wild fish populations nearby. Aside from taking a toll on the natural fish populations, diseases indirectly harm the natural environment because they prompt a more liberal usage of pesticides and antibiotics. One group that Dr. Lenihan studied in Norway, for example, sprayed entire bays with a pesticide to eliminate parasites. There are other, more sustainable ways to address disease, though. Some propose simply breeding animals that are less susceptible to disease, and others try to do aquaculture with smaller densities of fish, or in less fragile environments.

Once we’ve cleared the hurdle of infectious diseases, Dr. Lenihan and I shift our discussion to protein efficiency. The key component here is fine-tuning the protein feed-to-product ratio. This allows researchers to engineer the most efficient kinds of feed, and to breed the most efficient animals. As of today, aquaculturists have gotten this ratio down to 1:1—for every gram of protein the fish consumes, its meat offers a gram of protein. That’s 100% conversion efficiency—stellar, compared to land-based animal protein sources. Eggs topping the chart at 31% conversion efficiency for land-based protein sources, while on the lower end of the spectrum, beef has a measly conversion efficiency of 3%.

Hunter and his group are trying to make this process even more efficient by using vegetarian feed. This relies on the basic principle that growing vegetables is a lot more energy efficient than growing animals. The group Dr. Lenihan is working with, headed by Dr. Margareth Øverland, is feeding fish yeast from wood chips and algae and thanotropic bacteria. Dr. Øverland’s group, based out of the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, aims to develop even more efficient feeds. This university was also responsible for hybridizing the Atlantic Salmon, the same one we see at many grocery stores today.

Another aspect of his work is to determine whether the proteins that Øverland’s group is proposing have a lower environmental footprint than the best traditional feeds available on the market today. They do and that’s surprising, because over the past twenty years, salmon feed composition has sprung from 10% to 70% plant based—so you’d think how could we get better than plants?! Part of the reason for this shrunken environmental footprint of feeds is the transition from using human foods like soybeans to instead using microbial sources like yeast, which are far more productive. 10,000 times more productive, in fact.

Mollusks have an even lower carbon footprint, so for folks who like to do the most, this is the way to go. According to Dr. Lenihan, the best way to move forward is with filter feeders, like mussels or abalone. Abalone populations have had it rough recently, with their numbers sharply declining around the world. Most abalone industries, except those in California, have collapsed. These slow growing mollusks have been intensely overfished, and they’ve suffered from withering syndrome, a disease that spreads when the water warms. The focus of Lenihan’s research is to understand what populations of abalone were impacted, where, and to uncover the environmental triggers for withering disease. One way to combat this while raising farmed abalone is to select animals that are resistant to disease when creating a hatchery program. It looks like the main trigger for withering disease is stress. The abalone that live in the tidal zone are exposed to air every day, and this stresses them out and makes them more susceptible to disease.

The most important finding so far, says Dr. Lenihan, is that we can mix disease epidemiology and ecology—realizing that the best way to maintain a healthy farmed abalone population is to remove most of the diseased organisms (which are still safe for human consumption) to prevent contagion and keep the population strong and healthy. This approach is counterintuitive, which makes it all the more important. Leaving a population alone is worse than continuing harvest or doing planned harvest. “And that’s the value of science,” Lenihan says, “Because science doesn’t just take the knee-jerk reaction of what you think is right.”

Another big challenge facing aquaculture today is that existing management programs, for the most part, take a one-size-fits-all regulatory approach. And recently, the tide of opinion has turned against this method. “There’s been a big shift in the environmental NGO world,” Dr. Lenihan tells me, “from ‘we need to be making reserves,’ to “we can’t be making reserves everywhere, so how do we manage the population of fish and other organisms in a sustainable way?’ And the way we’re doing that is through collaborative, community-based fisheries.”

His perspective, needless to say, is not universal. Focusing on short-term gains while largely disregarding long-term consequences is the modus operandi for folks around the world. In Chile, for example, overcrowded (though temporarily profitable) fjord-fisheries were inevitably hit with disease and completely wiped out. Meanwhile, Chinese grouper fisheries are trying to set up big cages of their fish in Polynesian lagoons, all destined to be shipped back to China. This is largely unsustainable, focused solely on the short-term economic benefits of the program. These businesspeople aren’t acknowledging the inevitable consequences of overcrowding, like disease and population decimation. Any fish scientist, it’s safe to say, would not recommend this course of action. They’re doing it anyway. It’s profitable, for now. This mindset, which Hunter terms “anti-science”, dominates our government too. Many of our own businesses treat science-based regulations as just another way to reduce their bottom line. The idea, from their perspective, is that they’ll make less money if regulators curtail human activity in the environment. But Hunter insists this isn’t true. Hunter adds that while short-term growth may always look good from the business perspective, “It’s not a given that it’s a good thing all the time.” Short term growth can indicate fragility—often, it’s just too good to be true.

His cumulative research experience calls for widespread yet individualized, ‘habitat-based’, fisheries management. This big-picture approach assesses all aspects of the habitats they’re working with: changes in temperature, common diseases, neighboring species, natural predators, environmental stressors, etc. This is opposed to the traditional management style, which only looks at one species by itself. NOAA provides a good example of what they call ‘ecosystem-based’ management. “if a particular species’ population is declining, fishery managers might reduce the annual catch limit the following year in an attempt to reduce overexploitation,” the article begins, tracing the traditional approach. “However, fishing is only one variable affecting a species’ population. Additional elements come into play, such as interactions with other species, the effects of environmental changes, or pollution and other stresses on habitat and water quality.”

That’s why scientists and management and other community members have to unite to solve these problems. That’s the whole directive behind community-based management, which incorporates citizen feedback into the decision-making process. For example, a group of rock crab fishermen in Santa Barbara contacted the Bren School of Environmental Science & management for help after noticing that the population seemed in worse shape than regulators had predicted. “They [the fisherman] learned how to collect information that would feed back into management models that would help them control how much they should fish, where and when they should fish.” Dr. Lenihan told me, “so that’s what collaborative management is, it’s integrating the fishermen that are out on the ocean, seeing things every day and getting data, and using that to manage themselves.” The people actually out there on the water are a valuable source of information. When these three groups don’t cooperate effectively, we end up with tragically inefficient management systems.

And it’s not a matter of technology, Hunter promises. “We can figure out the solutions. We have the technology. It’s a matter of will. It’s a matter of designing management programs that actually work.” This goal—getting scientists, management, and fishermen to work together smoothly, is as much a priority for Bren as it is for Dr. Lenihan himself. As he tells me, sounding slightly relieved, he’s in the right place. “Frankly, that’s what the Bren school’s all about.”

©2019 Natalie Overton

Dr. Lisa Straatton and her team at the Cheadle Center for Biodiversity & Ecological Restoration (CCBER) have embarked on a mission to transform a golf course into a diverse restored habitat: an estuary teeming with native species, a space for passive recreation and active research for UCSB students and faculty. Even better, it’s specially graded to withstand the sea level rise that the Santa Barbara community is bracing for in years to come.

|

Dr. Stratton isn’t new to the area. She’s been running CCBER since 2005. So when she spotted this golf course, she saw its potential to benefit the surrounding community. This patch of land, which is now called the North Campus Open Space (NCOS) project, was an estuary in the 1870s, but was filled in and built up to serve as a golf course in the 1960s. Dr. Stratton and CCBER are now bringing the area back to something close to its original state , but this patch of green wasn’t their focus at first. |

Initially, she and her team were set to restore the South Parcel, a 68 acre piece of land which UCSB agreed would be restored, not developed into housing, in the Ellwood-Devereux Joint Proposal. Looking at the maps of the area, Dr. Stratton realized that a neighboring golf course was locked in by housing and the South Parcel, and that any future effort to restore the golf course would be too expensive after the development of the south parcel. “Given how degraded this was,” Dr. Stratton told me, “before we started spending any money, we first had to see if we could restore this wetland and take the excavated soil back on to South Parcel.”

Back in 2008, Lisa partnered with the Trust for Public Land (TPL) who were able to buy the golf course. “It was during that exact time [the 2008 recession] that we were approaching them to buy it, so conditions were prime”, says Dr. Stratton In 2013, the TPL finished gathering up all the grants, which amounted to $7 million. After a long cooperative process of meetings, grant applications, and deed restrictions, the land was set to be restored.

As it stands now, portions of the area that were part of the original estuary are now developed with housing, so she couldn’t restore the entire space back to the original version. There were other differences this time around, too. For example, we now have an urban watershed, which means that runoff doesn’t soak into the land, and is partially delivered through storm drains into the estuary. Because extra water, whether via heavy rains or sea level rise, doesn’t have anywhere to go in the current system, Dr. Stratton’s design creates more flexibility for the system. “We’ve created intermediate zones for the stormwater to come in and be treated before it gets to the wetlands,” Dr. Stratton said, “so we have water quality benefits downstream.”

As mentioned above, the NCOS project has lowered local flood risk by removing up to eight feet of dirt from this wetland, creating a place for stormwater to go. The county has certified that the project has lowered the flood zone in the surrounding area by two feet, thus taking all the residents living near the area out of the flood zone. The benefits of this development include saving Goleta community members money on flood insurance, limiting closures of Storke road, and avoiding seasonal flooding of nearby buildings, like the Meadow Tree and Fairview apartments.

The estuary will also serve as a haven for many endangered species, complete with nesting grounds for the western snowy plover. It will also incorporate little side channels for tidewater gobies to ensure they are protected from being swept away when the mouth of the estuary breaches and all the water rushes out to sea. Nearby, the CCBER team is planting upwards of twenty acres of salt marsh vegetation, which sequesters carbon while serving as habitat for endangered and non-endangered species alike.

CCBER has established two main goals for the project: to restore the land, and to support social values. Part of restoring the land includes maintaining a balance of a variety of ecosystems despite future sea level rise, while simultaneously providing space for passive recreation and research. To accomplish this, Dr. Stratton and her team are attempting to preserve and restore the historical flora of the area. “We collected the seeds to grow every plant we’re planting here,” Dr. Stratton adds, “so we know where all the genotypes are from.”

One day, about 18 months ago, the entire golf course was dug out and graded to withstand up to eight feet of sea level rise. This opens up space, called transgression space, which protects the balance of the varied habitats (salt marsh, mudflats, sub-tidal) within the estuary, retaining 15-25% salt marsh and mitigating the sea level rise experienced in the surrounding areas. This was integral in the design of the whole project, which has ensured room for all three kinds of estuarine habitats. It’s not fully tidal, it’s an intermittently tidal estuary, but these gentle slopes also support accretion, the slow buildup of sediment and organic matter, allowing the salt marsh to build up a bit with each tide. All this grading also expands the tidal prism—a technical term referring to the amount of water that can flow in and out of the estuary with each change of tide. The increased size of the wetland, since restoration significantly increases the tidal prism of the estuary, and with sea level rise the system is modeled to transform from an intermittently open estuary to a fully tidal estuary.

This is great news for adjacent homeowners, whose backyards and doorsteps will be 3 feet less flooded by sea level rise. At the opening of the estuary, a beach berm partially blocks the in-and-out flow of the tides. Without the project, the berm would build up, leading to higher water levels, and, you guessed it, more flooding. However, the expanded tidal prism allows a higher volume of water to rush in and out regularly, so the berm would be constantly in flux until it becomes fully tidal.

In addition to removing and recontouring tons of dirt within the North Campus Open Space, the team buried 200 tons of a pyrolyzed wood carbon equivalent, called biochar, about twelve inches beneath the surface of the restored mesa. The carbon crystals in the biochar don’t decompose, so they serve as nuclei for biotic activity within the dense, salty, nutrient poor clay soils excavated from the estuary and used to create the mesa. In addition to directly storing 200 tons of carbon, it creates an opportunity for biotic activity that’s beneficial for plants, urging them to put better roots down, which sequesters even more carbon. This carbon-storing cycle will continue indefinitely beneath the perennial grassland that will soon cover these slopes.

There is one more added benefit: groundwater recharge. “Before, freshwater wouldn’t have had a place to stay,” Dr. Stratton explains. But with the grading and expansion of wetland, “now we’ve doubled the capacity of the system.” Allowing for rain and runoff to filter through the estuary before pouring into the sea keeps the water on land for longer. This allows more time for plants and dirt to absorb it, instead of, as Dr. Stratton puts it, “dumping all of our fresh rainwater straight into the ocean, the way storm drains do.”

As a continuation of their success in K-12 Kids in Nature programs, CCBER kicked off the ‘safe route to school project’ on October 10th, 2018. This initiative opens access to paths running through the space for the children in the community who would otherwise be biking to school on a road busy with cars. This is all part of a broader trend for CCBER, according to Dr. Stratton, in which the organization has been branching out into the community: “CCBER has been pretty much focused on main campus and UC Santa Barbara students,” she says, “but this project is really out there in terms of being in the community.”

She’s smiling widely now, almost glowing with the satisfaction this project seems to have brought her. In her office jam-packed with rolled-up maps and stacks of papers, Dr. Stratton shares her hopes for the project, which envision the campus and community hand-in-hand. She and her team, not to mention the countless campus organizations pitching in, have contributed to what she calls “a whole new thing for campus”, and one which has expanded CCBER’s orientation to be more inclusive of the public. Her confidence in these statements come from the excitement she’s sensed in the UCSB and local community: “It’s been rewarding to see how people appreciate it,” but that wasn’t her motivation all along. “You get pretty focused on the amazing opportunity to bring back something that was so degraded.”

©2019 Natalie Overton

Our Monthly Get-Together: Eco Nerd Night!

Every month, on a Tuesday night in Isla Vista, we bring sustainability researchers and faculty to you! Like-minded (or different-minded) individuals from across our campus and neighborhood gather to feed their minds and bodies with a talk, a discussion, and some free pizza. Our atmosphere is lighthearted, casual, and curiosity-fueled. Our goal is to send you home with an inspired mind, some new friends, and a full stomach.

To learn more about this month’s event, or to make sure you stay in the loop, visit and like Eco Nerd Night’s Facebook page.

https://www.facebook.com/EcoNerdNight/

We hope to see you there!